Murder & Trial

The most grizly topic in the Parker/Hulme case, please remember: it is a real-life tragedy.Murder

June 22, 1954“The Day of The Happy Event. I am writing a little of this up in the morning before the death. I felt very excited and ‘The night before Christmas-ish’ last night. I did not have pleasant dreams though. I am about to rise” - from Pauline Parker's diary

Events of June 22, 1954

The morning of June 22, 1954. 10.30am. Juliet Hulme collected half a brick from a pile next to the garage at her Ilam home. She was then driven into Christchurch city to do some “personal shopping” by her mother. Hilda Hulme described Juliet as happy, calm and affectionate that morning.

At 11am, Juliet arrived at Pauline Parker’s house. Both girls made small talk with Honorah Parker, before making their way up to Pauline’s room. There they placed the half-brick into a stocking and knotted it. Pauline placed this into her school shoulder bag. Juliet had brought the small pink stone that she had removed from a brooch.

At 12pm, Pauline’s father Herbert Rieper and her sister Wendy arrived home from work, for lunch. Juliet and Pauline joined them. This was reportedly a happy affair, with laughing, jokes and warmth between the family.

At 1.30pm, Honorah Parker left with Pauline and Juliet on a bus to Victoria Park in the Cashmere Hills.

At 2.35pm, the trio arrived in Victoria Park terminus and exited the bus. Honorah was feeling a little parched. She decided to go to the nearby ‘Tea Kiosk’. Inside Honorah ordered a pot of tea and the girls ordered soft drinks. They were served by Agnes Ritchie; the manager of the kiosk. Agnes stated later that she chatted with Honorah for a bit and that the girls behaved cordially when she addressed them. She concluded that she had thought they were a quiet group.

At 2.35pm, the trio arrived in Victoria Park terminus and exited the bus. Honorah was feeling a little parched. She decided to go to the nearby ‘Tea Kiosk’. Inside Honorah ordered a pot of tea and the girls ordered soft drinks. They were served by Agnes Ritchie; the manager of the kiosk. Agnes stated later that she chatted with Honorah for a bit and that the girls behaved cordially when she addressed them. She concluded that she had thought they were a quiet group.3.05pm. Honorah, Pauline and Juliet all left the tea kiosk. They entered Victoria Park through a gap in the stone wall and set off along the steep path. The east side bush track, as it was known.

At 3.20pm. 130m down the path they came to a small wooden bridge. Juliet took the lead. Honorah followed with Pauline at the rear. Juliet got far enough ahead to initiate the ‘plan’. She dropped the pink stone on the ground. Then she called for Honorah and Pauline to come see what she found. Honorah lent down to look at the stone. Pauline removed the brick in the stocking from her shoulder bag.

Peter Graham is a true crime writer from Canterbury and author of ‘So Brilliantly Clever’; a detailed investigation into the Parker-Hulme murders in which he spent three years travelling the world researching the case. Graham in his book ‘So Brilliantly Clever’ describes in detail what happened next:

Peter Graham is a true crime writer from Canterbury and author of ‘So Brilliantly Clever’; a detailed investigation into the Parker-Hulme murders in which he spent three years travelling the world researching the case. Graham in his book ‘So Brilliantly Clever’ describes in detail what happened next:

“Pauline, coming from behind swung the brick as hard as she could at her mother’s skull. Nora yelled and instinctively covered her head with her hands. She was now fighting for her life. Pauline bashed away mercilessly but her mother was slow to go down. She and Juliet forced her to the ground. Juliet grabbed the loaded stocking from Pauline and landed further furious blows on Nora’s head. Blood was spraying everywhere. Her resistance was weakening. The stocking broke. Nora was now lying face upwards making a terrible noise. Juliet kneeled, gripped her around the throat and held her head against the ground with Pauline, grasping the half-brick in her hand, hammered her again and again and again – on the forehead, the temples, wherever she could land a blow. Nora writhed and twisted, then twitched convulsively. They tried to drag her to a place where they could roll her down a bank but she was already a dead weight. It was all they could do to shift her a few feet. She was gurgling blood as they left.”

“Pauline, coming from behind swung the brick as hard as she could at her mother’s skull. Nora yelled and instinctively covered her head with her hands. She was now fighting for her life. Pauline bashed away mercilessly but her mother was slow to go down. She and Juliet forced her to the ground. Juliet grabbed the loaded stocking from Pauline and landed further furious blows on Nora’s head. Blood was spraying everywhere. Her resistance was weakening. The stocking broke. Nora was now lying face upwards making a terrible noise. Juliet kneeled, gripped her around the throat and held her head against the ground with Pauline, grasping the half-brick in her hand, hammered her again and again and again – on the forehead, the temples, wherever she could land a blow. Nora writhed and twisted, then twitched convulsively. They tried to drag her to a place where they could roll her down a bank but she was already a dead weight. It was all they could do to shift her a few feet. She was gurgling blood as they left.”

3:30pm. Pauline and Juliet arrived back at the tea kiosk with bloodsoaked clothing, white-faced and hysterical. Juliet had a lot of blood on her hands with a fine mist of blood on her face. Pauline had an abundance of blood on her face and hands; her left hand was covered in gore. Pauline, panicked managing to blurt out “Please, could somebody help us? Mummy has been hurt! It’s Mummy, she’s terribly hurt! She’s dead!” Juliet added “It’s her mother, she’s hurt! She’s covered with blood. Please, somebody help!”.

3:30pm. Pauline and Juliet arrived back at the tea kiosk with bloodsoaked clothing, white-faced and hysterical. Juliet had a lot of blood on her hands with a fine mist of blood on her face. Pauline had an abundance of blood on her face and hands; her left hand was covered in gore. Pauline, panicked managing to blurt out “Please, could somebody help us? Mummy has been hurt! It’s Mummy, she’s terribly hurt! She’s dead!” Juliet added “It’s her mother, she’s hurt! She’s covered with blood. Please, somebody help!”.

Kenneth Ritchie, Agnes’ husband then searched and found the body. Agnes then phoned for a doctor and an ambulance. Pauline and Juliet then washed off the blood and both asked for their fathers. Agnes then phoned Herbert Rieper at Dennis Brothers’ Fish Supply, his work, but he was not in the shop and she left a message. Then Agnes phoned Henry Hulme and he said he would come immediately. Anges then brought Pauline and Juliet hot tea with much sugar. She noted that Pauline gulped down the hot tea with no milk, oblivious to the temperature and apparently in shock. Juliet was noted to be talking rapidly and hysterically. Anges asked how the accident occured. Pauline answered in a slow voice “She slipped on a plank and hit her head on a brick. Her head kept bumping and banging as it fell”. Juliet intervened “Don’t think about it. It’s only a dream. We’ll wake up soon. Let’s talk about something else.” After a long lull, Pauline groaned loudly “Mummy, she’s dead.”

Kenneth Ritchie, Agnes’ husband then searched and found the body. Agnes then phoned for a doctor and an ambulance. Pauline and Juliet then washed off the blood and both asked for their fathers. Agnes then phoned Herbert Rieper at Dennis Brothers’ Fish Supply, his work, but he was not in the shop and she left a message. Then Agnes phoned Henry Hulme and he said he would come immediately. Anges then brought Pauline and Juliet hot tea with much sugar. She noted that Pauline gulped down the hot tea with no milk, oblivious to the temperature and apparently in shock. Juliet was noted to be talking rapidly and hysterically. Anges asked how the accident occured. Pauline answered in a slow voice “She slipped on a plank and hit her head on a brick. Her head kept bumping and banging as it fell”. Juliet intervened “Don’t think about it. It’s only a dream. We’ll wake up soon. Let’s talk about something else.” After a long lull, Pauline groaned loudly “Mummy, she’s dead.”At 4pm, Dr. Hulme arrived at the kiosk. He told Agnes Ritchie to tell the police he was taking Pauline and Juliet to his home in Ilam.

4.30pm. Dr. Hulme arrived home with the two girls. Hilda Hulme then bathed Pauline and Juliet and treated them for shock, fed them and then sent them to bed.

At 8pm, two Detectives; Senior Detective Brown and Detective Sergeant Tate arrived at the Hulmes Ilam home. The two detectives interviewed Pauline and Juliet. Pauline gave this account of what had happened “We were walking up the track having been to the bottom. I was leading and mother and Deborah were behind me. Mother suddenly slipped and fell. She twisted sideways and hit her head on a rock or something. She seemed to keep tossing up and down and hitting her head.” Juliet backed up this story in her interview. Then when Pauline was asked about a bloody stocking found at the crime scene she appeared taken aback “We didn’t take mother’s stockings off, I was wearing sockettes. I had an old stocking in my bag. I used it to wipe up the blood.” Then Detective Tate was informed that Juliet would like to make a second statement. He left to go take her statement as Detective Brown stayed with Pauline.

At 8pm, two Detectives; Senior Detective Brown and Detective Sergeant Tate arrived at the Hulmes Ilam home. The two detectives interviewed Pauline and Juliet. Pauline gave this account of what had happened “We were walking up the track having been to the bottom. I was leading and mother and Deborah were behind me. Mother suddenly slipped and fell. She twisted sideways and hit her head on a rock or something. She seemed to keep tossing up and down and hitting her head.” Juliet backed up this story in her interview. Then when Pauline was asked about a bloody stocking found at the crime scene she appeared taken aback “We didn’t take mother’s stockings off, I was wearing sockettes. I had an old stocking in my bag. I used it to wipe up the blood.” Then Detective Tate was informed that Juliet would like to make a second statement. He left to go take her statement as Detective Brown stayed with Pauline.Juliet’s second statement claimed she didn’t witness the accident but had turned back after hearing voices to find Honorah Parker lying bloody on ground and she did not notice a brick or stocking. During this time Detective Brown was questioning Pauline. He stated to Pauline he thought Juliet was not involved in the incident, but she was. Pauline then started answering questions:

DETECTIVE BROWN: Who assaulted your mother?

PAULINE PARKER: I did.

DB: Why?

PP: If you don’t mind I won’t answer that question.

DB: When did you make up your mind to kill your mother?

PP: A few days ago.

DB: Did you tell anyone you were going to do it?

PP: No. My friend does not know anything about it. She was out of sight at the time. She had gone on ahead.

DB: What did your mother say?

PP: I would rather not answer that.

DB: How many times did you hit your mother?

PP: A good many times, I imagine.

DB: What did you use?

PP: A half-brick in a stocking. I took them with me for the purpose. I had the brick in my shoulder-bag. I wish to state that Juliet did not know of my intentions and she did not see me strike my mother. I took the chance to strike my mother while Juliet was away; I still do not wish to say why I killed my mother.

DB: Did you tell Juliet that you killed your mother?

PP: She knew nothing about it. As far as I know she believed what I told her, although she may have guessed what had happened, but I doubt it as we were both so shaken that it probably did not occur to her.

The confession concluded with:

PP: As soon as I started to strike my mother I regretted it but could not stop then.

Pauline Parker was charged with murder and taken to the Christchurch Police Station. Later that night Brown and Tate searched Pauline’s room with her father’s permission. There they found fourteen exercise books, a scrap book and two diaries. While Pauline was in Tate’s office she was seen writing on a piece of paper. When she finished, Tate confiscated the paper. It seemed to read as a diary entry.

Pauline Parker was charged with murder and taken to the Christchurch Police Station. Later that night Brown and Tate searched Pauline’s room with her father’s permission. There they found fourteen exercise books, a scrap book and two diaries. While Pauline was in Tate’s office she was seen writing on a piece of paper. When she finished, Tate confiscated the paper. It seemed to read as a diary entry.June 22, 1954

“I have successfully committed moider. Found myself in an unexpected place. All the Hulmes have been wonderfully kind and sympathetic. Anyone would think I’d been good. I’ve had a pleasant time with the police talking nineteen to the dozen and behaving as though I hadn’t a care in the world. I haven’t had a chance to talk to Deborah properly but I am taking the blame for everything”

The cold facts

Post Mortem: Performed by Dr Colin Thomas Bushby Pearson on June 23, 1954. The cause of death was shock associated with multiple wounds of the head and fractures of the skull.

Post Mortem: Performed by Dr Colin Thomas Bushby Pearson on June 23, 1954. The cause of death was shock associated with multiple wounds of the head and fractures of the skull.Forensic: Dr Pearson testified he examined the body of Honora Parker when the body was lying in the plantation at Victoria Park, around 7:30 pm, June 22, 1954. Rigidity had not set in. There were multiple lacerated wounds on the head and face and minor injuries on the fingers. Dr Pearson stated there were 45 discernable injuries on the body, (head, neck, face and hands), 24 of them being lacerated wounds on the face and head [note: Some popular accounts mistakenly state 69 total injuries. jp] Some wounds were minor but many were serious. The head wounds varied in size and shape and some had ragged edges and showed crushing and bruising at the edges. They had been inflicted by a blunt instrument applied with considerable force. In the front of the skull the fractures were were extensive. There were haemorrhages on the brain. The fractures of the skull indicated that the victim's head was most probably immobilized on the ground when the force was applied. It would have taken only a few of these major head wounds to produce unconsciousness. He could not say in what order the wounds were received. In cross-examination he testified it was possible that a single blow could produce a number of lacerated wounds. Bruises on the neck suggested that the victim was held forcibly by the throat, but there was no suggestion of throttling. The lacerations on the fingers could have been caused when the victim put up her hand to defend herself. The injuries could have been produced by the half-brick produced in Court. The half-brick, the stocking foot and the stocking leg minus the foot all had human bloodstains. Human hairs similar in texture to those from the head of the dead woman were adhering to the stocking foot.

Constable William McDonald Ramage, police photographer went about 7 pm went to Victoria Park and took photos there. On June 23 he was present during the post mortem examination of the body and took photos then of Honora Parker's body. These and other photos were entered into evidence, under objection of defense counsel.

Constable William McDonald Ramage, police photographer went about 7 pm went to Victoria Park and took photos there. On June 23 he was present during the post mortem examination of the body and took photos then of Honora Parker's body. These and other photos were entered into evidence, under objection of defense counsel.Mr Kenneth Ritchie testified that he found the victim's body, lying on her back with the feet pointing uphill. Her head was badly battered. There was blood on her head and face and on the path. Her skirt was up a little at the knees and he pulled it back down.

Dr Donald Walker was the first physician called to the scene, arriving shortly before 4 pm. He observed that the victim's head was thrown back and was lying downhill. There was no doubt about her being dead. There was a lower denture lying on the ground to the victim's left alongside the jaw. The stockings were muddy and smeared with blood. Her arms were mud- and blood-stained. The eyes were closed but gave the impression they had been blackened. There were severe gashes on the victim's head and a great deal of blood had streamed from her head, had flowed down the path and had congealed. (Victim was almost completely ex-sanguinated so bleeding from head was massive and rapid [note: Possibly indicating severed carotid artery, which might also explain the massive amount of spattered blood on PYP and JMH. jp].) From the appearance of the body Dr Walker could not reconcile it with an accident. One shoe was off and personal articles were strewn nearby.

Sgt Robert Hope testified there was a stream of blood 10 or 12 ft downhill from the head. Various objects were strewn about near the body. There was a half-brick lying about 15 inches from the body. Sgt Hope also found a woman's lisle stocking on a bank. In a shallow drain beside the bank there was a large pool of blood.

Most major wounds were on the right side and front of the head. Victim's right ear was badly split. Some reports indicate severe cosmetic damage to face, others that wounds on left side of head and face were less severe. Mouth was blocked with vomit, possibly indicating convulsions.

Weapon: Half-brick in knotted woman's lisle stocking, the brick was ejected by the force of the blows. Victim's hair found on stocking. Brick probably used as weapon after ejection from stocking. Bloody stocking and brick recovered separately at scene, near the body.

The aftermath

23 June, 1954. “I am taking the blame for everything”. This sentence suddenly put attention back on Juliet. Along with this, Brown and Tate found enough evidence in the diaries to justify interrogating Juliet once more. They returned to Ilam to interview Juliet. Her statement changed once more “We went to a spot well down one of the paths and Mrs Parker decided to come back. On the way back I was walking in front. I was expecting Mrs Parker to be attacked. I heard noises behind me. It was loud conversation in anger. I saw Mrs Parker in a sort of squatting position. They were quarreling. I went back. I saw Pauline hit Mrs Parker with the brick in the stocking. I took the stocking and hit her too. I was terrified. I thought that one of them had to die. I wanted to help Pauline. It was terrible. Mrs Parker moved convulsively. We both held her. She was still when we left her. The brick had come out of the stocking with the force of the blows. I cannot remember Mrs Parker saying anything distinctly. I was too frightened to listen. After the first blow was struck I knew it would be necessary to kill her. I was terrified and hysterical.” Juliet was arrested and charged with murder.

One day later, Honorah’s body was cremated while Juliet and Pauline were reunited in Paparua Prison. There, they listened to classical music, took long walks together and wrote voluminously.

One day later, Honorah’s body was cremated while Juliet and Pauline were reunited in Paparua Prison. There, they listened to classical music, took long walks together and wrote voluminously.Dr Reginald Medlicott was one of the psychiatrists who interviewed the two girls on June 27 and June 28. After these interviews Dr Medlicott told a friend he had never encountered such pure evil as he had in those two girls.

1 July 1954. Juliet was visited by her father Henry Hulme in Paparua prison. He tells her he is leaving New Zealand for England. Henry stated later that the meeting was only a few minutes long and that when he kissed Juliet goodbye, she told him, “I want you to go”. The next day Dr. Hulme executed his plan of leaving his wife and her lover and taking their son back home to England. On the voyage home he wrote “The world will just have to think of me as an unnatural father. I cannot say why I decided to leave New Zealand at this time. It would involve too many people. But there is nothing I can do there just now. My only concern now is for my son. I want to spare him all I can. I’ve told him his sister is mentally ill–as indeed she is.”

The hearing at Magistrate's Court

16 july 1954. A preliminary Hearing and Inquest at a Magistrate's Court resulted in Pauline and Juliet being ordered to stand trial on murder charges in relation to the death of of Pauline's mother. They were committed for trial by jury in the Supreme Court of New Zealand. The trial was set for August 23rd, 1954.

16 july 1954. A preliminary Hearing and Inquest at a Magistrate's Court resulted in Pauline and Juliet being ordered to stand trial on murder charges in relation to the death of of Pauline's mother. They were committed for trial by jury in the Supreme Court of New Zealand. The trial was set for August 23rd, 1954.

"A large crowd, mostly women, queued in poring rain yesterday outside Christchurch Magistrate's Court awaiting the appearnce of two teen-age girlds charged with murdering the mother of one of them."

"A large crowd, mostly women, queued in poring rain yesterday outside Christchurch Magistrate's Court awaiting the appearnce of two teen-age girlds charged with murdering the mother of one of them."

Pauline's father, Herbert Rieper, also testifies, "...Last month Pauline stayed for 10 days with Juliet and we picked her up in the car and brought her home the Sunday before the tragedy. Pauline was brighter and joined in the conversation more than she usually did. She sat in front of the fire writing and said she was writing an opera.

Pauline's father, Herbert Rieper, also testifies, "...Last month Pauline stayed for 10 days with Juliet and we picked her up in the car and brought her home the Sunday before the tragedy. Pauline was brighter and joined in the conversation more than she usually did. She sat in front of the fire writing and said she was writing an opera.When I went home on the Monday I was pleased when her mother said what bright company Pauline had been and how much work she had done. She said that they were going out together the next day because Pauline would begin work the following Monday. I learned that Juliet Hulme was going with them. When I went home at lunch time on the Tuesday Juliet Hulme was there and it was quite bright. The girls were happy and joking...".

Waiting for trial

From the 6th to the 14th of August, the girls were visited by Dr Francis Bennet, another psychiatrist. Peter Graham writes about this visit in his book ‘So Brilliantly Clever’. “Dr Francis Bennett, was shocked that neither girl showed any contrition for Nora Rieper’s death. “There’s nothing in death” Juliet said loftily. “After all, she wasn’t a very happy woman. The day we killed her I think she knew beforehand what was going to happen and didn’t seem to bear any grudge.” Asked if she had any regrets she replied, “None whatever. … Of course we did not want my family to get involved in this but have both been terribly happy since it happened, so it has all been a blessing in disguise.” Pauline, likewise, was sorry for the trouble she had brought to the Hulme household but had no regrets about her mother. She would willingly kill her again if she were a threat to her relationship with Juliet.”

Trial

23 August 1954. The first day of the five day trial commenced in the Supreme Court of New Zealand in Christchurch. "The first onlookers were trying the doors of the Court at 8 a.m., and by 9 a.m. their number had grown to a couple of dozen, all women with the exception of two young men. To avoid sightseers the girls were brought to Court early, arriving a few minutes after 9 a.m., and the van was backed up against the doorway, through which the girls were taken into Court and upstairs to the cells. . . . When the doors of the gallery opened sixty people streamed into the three front rows. The gallery was not full."

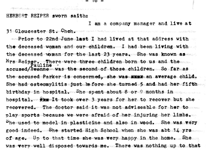

23 August 1954. The first day of the five day trial commenced in the Supreme Court of New Zealand in Christchurch. "The first onlookers were trying the doors of the Court at 8 a.m., and by 9 a.m. their number had grown to a couple of dozen, all women with the exception of two young men. To avoid sightseers the girls were brought to Court early, arriving a few minutes after 9 a.m., and the van was backed up against the doorway, through which the girls were taken into Court and upstairs to the cells. . . . When the doors of the gallery opened sixty people streamed into the three front rows. The gallery was not full." Proceedings overseen by Judge Francis Boyd Adams began on August 23, lasting six days. Alan Brown led the prosecution, assisted by Peter Thomas Mahon. Hulme’s defense was providedby Terrance Arbuthnot Gresson assisted by Brian McLelland, with Alec Haslam, assisted by J. A. Wicks, representing Parker. The motive for the killing was identified as impending separation of the two young women aggravated by Honora’s refusal to permit her daughter to leave New Zealand with Hulme. The defense sought to prove insanity in terms of Section 43 of the New Zealand Crimes Act 1908, a defense based on the 1843 M’Naghten rules. As such, Gresson and Haslam were burdened with the task of proving that at the time the murder took place, Parker and Hulme were laboring under “disease of the mind to such an extent as to render [them] incapable of understanding the nature and quality of the act or omission, and of knowing that such an act or omission was wrong,” consistent with the second clause of the 1908 Act. Both defense and prosecution called medical witnesses. Reginald Warren Medlicott, a psychiatrist, and Francis Oswald Bennett, a general practitioner, spoke for the defense, arguing that the girls were suffering from a form of insanity which left the pair deluded across a number of facets, including their belief that murdering Honorah would result in the preservation of their friendship. Crown medical witnesses were Kenneth Robin Stallworthy, a senior medical advisor to Auckland’s Avondale Mental Hospital, and James Edwin Savill and James Dewar Hunter, a medical officer and superintendent, respectively, at Christchurch’s psychiatric hospital, Sunnyside.

Proceedings overseen by Judge Francis Boyd Adams began on August 23, lasting six days. Alan Brown led the prosecution, assisted by Peter Thomas Mahon. Hulme’s defense was providedby Terrance Arbuthnot Gresson assisted by Brian McLelland, with Alec Haslam, assisted by J. A. Wicks, representing Parker. The motive for the killing was identified as impending separation of the two young women aggravated by Honora’s refusal to permit her daughter to leave New Zealand with Hulme. The defense sought to prove insanity in terms of Section 43 of the New Zealand Crimes Act 1908, a defense based on the 1843 M’Naghten rules. As such, Gresson and Haslam were burdened with the task of proving that at the time the murder took place, Parker and Hulme were laboring under “disease of the mind to such an extent as to render [them] incapable of understanding the nature and quality of the act or omission, and of knowing that such an act or omission was wrong,” consistent with the second clause of the 1908 Act. Both defense and prosecution called medical witnesses. Reginald Warren Medlicott, a psychiatrist, and Francis Oswald Bennett, a general practitioner, spoke for the defense, arguing that the girls were suffering from a form of insanity which left the pair deluded across a number of facets, including their belief that murdering Honorah would result in the preservation of their friendship. Crown medical witnesses were Kenneth Robin Stallworthy, a senior medical advisor to Auckland’s Avondale Mental Hospital, and James Edwin Savill and James Dewar Hunter, a medical officer and superintendent, respectively, at Christchurch’s psychiatric hospital, Sunnyside.

Brian McClelland was junior defence counsel for Terence Gresson in defending Juliet Hulme. Much of the legwork in preparing her defence was his. "I read all the material. I interviewed her, Terence did too, but not nearly as much." "When the killing happened they had not called on Terence at all. They let Juliet be interviewed by Detective Archie Tate. She had made a statement admitting that she had taken part in the killing. We couldn't move a yard on the facts."

Brian McClelland was junior defence counsel for Terence Gresson in defending Juliet Hulme. Much of the legwork in preparing her defence was his. "I read all the material. I interviewed her, Terence did too, but not nearly as much." "When the killing happened they had not called on Terence at all. They let Juliet be interviewed by Detective Archie Tate. She had made a statement admitting that she had taken part in the killing. We couldn't move a yard on the facts.""Juliet was in custody and we had trouble because Hilda Hulme, the mother was a Crown witness. She had to give evidence about what Juliet had done before she went up to the hills. But we wanted to see her because, of course, our defence was that she was insane." "We had to get the background from someone. The police did not want us to interview the mother at all."

Terence Gresson was a Cambridge graduate and an old friend of Henry Hulme. After the trial McClelland felt Gresson had not made a strong enough pitch to the jury's emotions.

The defence did not dispute that Parker and Hulme carried out the killing. Claiming the girls were insane at the time of Mrs Parker’s death “The Crown has seen fit to refer to the accused as ordinary dirty-minded little girls. Our evidence will show that they are nothing of the kind. The Crown’s description is unfortunate and medically incorrect. They are mentally sick girls more to be pitied than to be blamed.”

This is when Dr Reginald Medlicott; the psychiatrist who interviewed them in prison took the stand. “I consider they have paranoia of an exalted type and it is in the setting of a folie a deux, It is a form of systemised delusional insanity. It can be of various types, the usual being the prosecutorial type but the girls suffer from the exalted type. The French phrase folie a deux is used to describe a communicative insanity. Both are sensitive, self-contained, imaginative, selfish, – and showed inability to accept criticism. Their association, I consider, proved tragic for them. There is evidence that their friendship became a homosexual one. There is no proof there was a physical relationship, although there is a lot of suggestive evidence from the diary that this occurred. There is evidence that they had baths together and had frequent talks on sexual matters. That is not a healthy relationship in itself, but more important, it prevents the development of adult sexual relationships. I don’t mean by that physical relationships, but attachment to people of the opposite sex. Homosexuality is frequently related to paranoia. When I first saw the two girls I knew that they were trying to prove themselves insane. In a very short time they had given me what they thought was proof of their insanity. This so-called proof consisted of compulsions, such as to thrust a hand into a fire but they never acted on them. They both said they were telepathic and got unusual communications – one to the other. They also said they had mood swings from exaltation to thoughts of suicide. I did not accept that and do not think they were convinced themselves. After a very short time with them I was definitely convinced they were insane. Their arrogance, like their conceit, was out of normal proportions. It was so severe I had to restrain myself. They consistently abused me. Parker told me I was an irritating fool and unpleasant to look at. Hulme pulled me over the coals for not talking sufficiently clearly. After I had physically examined Parker she shouted out, “I hope you break your flaming neck.” In the diaries you can cover Parker’s condition over the last 18 months. The whole thing rises to a fantastic crescendo. It would be difficult for anyone to read the 1954 diary and not feel that rising tension and exaltation. As the diary goes on evil becomes more and more important and one gets the feeling that they ultimately become helplessly under its sway. By June, 1954, both accused were grossly insane, I would say.”

This is when Dr Reginald Medlicott; the psychiatrist who interviewed them in prison took the stand. “I consider they have paranoia of an exalted type and it is in the setting of a folie a deux, It is a form of systemised delusional insanity. It can be of various types, the usual being the prosecutorial type but the girls suffer from the exalted type. The French phrase folie a deux is used to describe a communicative insanity. Both are sensitive, self-contained, imaginative, selfish, – and showed inability to accept criticism. Their association, I consider, proved tragic for them. There is evidence that their friendship became a homosexual one. There is no proof there was a physical relationship, although there is a lot of suggestive evidence from the diary that this occurred. There is evidence that they had baths together and had frequent talks on sexual matters. That is not a healthy relationship in itself, but more important, it prevents the development of adult sexual relationships. I don’t mean by that physical relationships, but attachment to people of the opposite sex. Homosexuality is frequently related to paranoia. When I first saw the two girls I knew that they were trying to prove themselves insane. In a very short time they had given me what they thought was proof of their insanity. This so-called proof consisted of compulsions, such as to thrust a hand into a fire but they never acted on them. They both said they were telepathic and got unusual communications – one to the other. They also said they had mood swings from exaltation to thoughts of suicide. I did not accept that and do not think they were convinced themselves. After a very short time with them I was definitely convinced they were insane. Their arrogance, like their conceit, was out of normal proportions. It was so severe I had to restrain myself. They consistently abused me. Parker told me I was an irritating fool and unpleasant to look at. Hulme pulled me over the coals for not talking sufficiently clearly. After I had physically examined Parker she shouted out, “I hope you break your flaming neck.” In the diaries you can cover Parker’s condition over the last 18 months. The whole thing rises to a fantastic crescendo. It would be difficult for anyone to read the 1954 diary and not feel that rising tension and exaltation. As the diary goes on evil becomes more and more important and one gets the feeling that they ultimately become helplessly under its sway. By June, 1954, both accused were grossly insane, I would say.” The crown argued vehemently against this. Prosecutor Alan Brown went so far as to question Medlicott mercilessly about the most minute details of his testimony. Following a non-answer from Medlicott, Brown read every entry from Pauline’s diary about trying to have sex with Nicholas. This served no purpose but to further insight prejudice against Pauline and to enrage Juliet to the point of derangement. The Sun-Herald reported “Juliet Hulme’s expression was savage. She leaned forward, grinding her teeth and spitting silent words through her rage-distorted lips” while Pauline bowed her head in shame. After nine hours of questioning, Medlicott was visibly nervous and had begun discrediting his own notes. When he was at last dismissed, Medlicott told McClelland “Alan Brown is certifiable. He will be in Ashburn Hall within two years.”, later telling a colleague that he was mad as the two girls.

The crown argued vehemently against this. Prosecutor Alan Brown went so far as to question Medlicott mercilessly about the most minute details of his testimony. Following a non-answer from Medlicott, Brown read every entry from Pauline’s diary about trying to have sex with Nicholas. This served no purpose but to further insight prejudice against Pauline and to enrage Juliet to the point of derangement. The Sun-Herald reported “Juliet Hulme’s expression was savage. She leaned forward, grinding her teeth and spitting silent words through her rage-distorted lips” while Pauline bowed her head in shame. After nine hours of questioning, Medlicott was visibly nervous and had begun discrediting his own notes. When he was at last dismissed, Medlicott told McClelland “Alan Brown is certifiable. He will be in Ashburn Hall within two years.”, later telling a colleague that he was mad as the two girls. Morale was low among the defense after their expert witness’ trouncing. They hoped dr. Francis Bennett would hold up better. Bennett echoed Medlicott’s diagnosis and analysis of the evidence in a more succinct manner, adding more details of the girls’ eccentricities and his own, more productive interviews.

Morale was low among the defense after their expert witness’ trouncing. They hoped dr. Francis Bennett would hold up better. Bennett echoed Medlicott’s diagnosis and analysis of the evidence in a more succinct manner, adding more details of the girls’ eccentricities and his own, more productive interviews.Bennett’s testimony had gone quite well and the defense was cautiously optimistic. However, it was time for cross-examination and prosecotor Alan Brown began with a manic fervor that could scarce be contained. He hammered Bennett with questions about the girls’ sexual relationship and whether they knew murder was legally wrong. Though his frenzy did not reach its crescendo until day five when he called the grandiosity of their writing into question, reading Shakespeare to prove they were not insane. He then began questioning Bennett about the girls’ religion before starting a raving line of questioning about Lady Macbeth’s behavior after the murder which had to be finished by Justice Adams as Brown had become overwrought and begun to cry. Bennett could scarce get a word in edge wise.

The Crown was bringing in their own experts who had interviewed the girls who argued they were in sound mind.

The Crown was bringing in their own experts who had interviewed the girls who argued they were in sound mind.During the trial psychiatrist Kenneth Stallworthy, witness for the Crown, spoke to diary entries proving that Parker recognized the nature and quality of the act leading up to the event, and retrospective interviews with the psychiatric specialist were also cited in court where Parker had claimed that “[w]e knew we were doing wrong. We knew we would be punished if we were caught and we did our best not to be caught.” Similarly Hulme was reported to have said, “I knew it was wrong to murder, and I knew at the time I was murdering somebody. You’d have to be an absolute moron not to know murder was against the law.”

Another weakness in the defence case was that the girls had claimed to be insane; people who were genuinly insane, Stallworthy contended, always insisted on saying they were sane.

The trial lasted six days. The girls were reportedly unremorseful during the entire trial and were reported by newspapers at the time to be smiling and giggling at times.

The trial lasted six days. The girls were reportedly unremorseful during the entire trial and were reported by newspapers at the time to be smiling and giggling at times. The all male jury reached their decision after a retirement of two hours and a quarter. They found that Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme were sane and found them guilty of murder. As they were too young for the death penalty, they were sentenced to imprisonment, to be detained at Her Majesty’s pleasure in separate institutions.

The all male jury reached their decision after a retirement of two hours and a quarter. They found that Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme were sane and found them guilty of murder. As they were too young for the death penalty, they were sentenced to imprisonment, to be detained at Her Majesty’s pleasure in separate institutions.His Honour's summing up took an hour and 20 minutes. When the foreman gave the unanimous verdict of the jury, a man in the public gallery upstairs stood up and called out: "Your Honour, I object." The Court crier called: "Silence," and the man was quickly hustled out of the gallery by the police. The two accused stood impassively in the dock from the time the jury returned with their verdict until after sentence was passed. At one stage Parker looked across at Hulme, whispered something and they both smiled.

There were about 125 persons present on Saturday, the sixth day of the trial. Some waited a considerable time outside the Court to see the girls leave the building but were disappointed. After the verdict had been announced his Honour said counsel would recall that he had drawn their attention to the fact that the question of the accuseds age might arise.

There were about 125 persons present on Saturday, the sixth day of the trial. Some waited a considerable time outside the Court to see the girls leave the building but were disappointed. After the verdict had been announced his Honour said counsel would recall that he had drawn their attention to the fact that the question of the accuseds age might arise.Counsel submitted that there was evidence of the age of each accused. His Honour then put it to the jury to rule on as a question of fact, and the foreman said they were all satisfied that each accused was under the age of 18. His Honour added to the record his own decision that they were both under 18.

His Honour conveyed to the jury the thanks of their country for their long and careful attention to the troublesome case with which they had had to deal for six days and which had meant enforced absence from their homes. It was usual to grant exemption from jury service for a period after such a case he said, but, as he knew many citizens were glad to serve their country such a way, he would not give a direction that all be exempted. Each member of the jury who desired exemption should inform the Registrar and a direction would be given that each such juror be exempt from jury service for three years.

The female police officer who escorted them from the court was shocked to overhear Juliet whisper to Pauline, "The old girl took a bit more killing than we thought". When the officer took her to task over the remark, Juliet jeered back, "Oh aren't we the perfect little policewoman".

Herbert Rieper stated from his home “I have nothing to say about it”.

Time in prison

Pauline Parker was moved from Paparua Prison in Christchurch to a Borstal north of Wellington; Arohata Women’s Reformatory. She was visited by her father once in her sentence here. He apparently did so reluctantly and summed up the experience later as “depressing”. During her time in prison she became devoutly Catholic. Juliet was flown to Auckland and taken to maximum security Mt Eden prison. She spent the first three months in solitary confinement. While she was at Mt Eden prison there were five hangings. Juliet was given harsher treatment by the Judge because she was considered the “more dominant personality and the leader of the two.” Prison was raw and brutal for Juliet. Juliet explains some of her experiences “During the day we did hard labour but I collapsed after two weeks and then I started sewing uniforms. I memorised the few books I had; screeds of the stuff. In prison we got little time alone except the nights — nights were a great blessing, not having to share a room. And when the light goes out and there’s nothing, then the light goes on inside your head.” The whole time she was incarcerated, Juilet received no visits from any member of her family, and their correspondence with her was infrequent. On September 12th, 1954, Walter Perry and Hilda Hulme left New Zealand. Perry said, speaking to press “We firmly believe Juliet is mad. Mrs Perry is sorry to leave Juliet, but she believes that Jonathan now has the greater need of her.”

Before leaving New Zealand Hilda Hulme showed her appreciation of Brian McClelland's efforts during the trying months surrounding the trial by presenting him with a Parker pen. "She didn't see the funny side of it," he says.

Five and a half years passed. On December 3rd, 1959, the NZ Secretary of State for Justice, announced that now twenty one year old Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme were released in an order some weeks earlier from prison and given new identities. “Neither girl knows where the other is living”. It is a myth their parole conditions specified they could not meet.

Press coverage

All newspaper articles from "The Press" about the murder and trial, in the july 17 ~ august 30 period. These are hi-res PDF files, with the whole page or pages, to read online or download and read on your own device.01 - the press - sat 17 july 1954 - p8

02 - the press - tue 24 august 1954 - p12

03 - the press - wed 25 august 1954 - p12_13

04 - the press - thu 26 august 1954 - p12

05 - the press - fri 27 august 1954 - p12_13

06 - the press - sat 28 august 1954 - p8

07 - the press - mon 30 august 1954 - p12

Sources:

- the Heavenly Creatures F.A.Q.

- Peter Graham, 'Anne Perry and the Murder of the Century' originally published as 'So Brilliantly Clever', 2011

- truecrimenz.com