Parker/Rieper family

It's complicated, as we would say today. The Rieper family situation was not so straightforward. And its delicate, we're talking about a murder...

Herbert Rieper

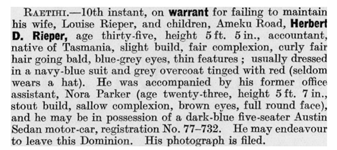

Herbert Detlev Rieper was born on October 22, 1894 in Strahan, Tasmania to Katie Thurza Stubbings and Claude Detlev Rieper, a shop assistant of German origin. He came to New Zealand in 1910, at the age of sixteen. At the outbreak of World War I, Herbert Rieper enlisted in the Army and was eventually stationed in Cairo, Egypt.

Herbert Detlev Rieper was born on October 22, 1894 in Strahan, Tasmania to Katie Thurza Stubbings and Claude Detlev Rieper, a shop assistant of German origin. He came to New Zealand in 1910, at the age of sixteen. At the outbreak of World War I, Herbert Rieper enlisted in the Army and was eventually stationed in Cairo, Egypt.While stationed in Cairo, Herbert Rieper met and married Louise McArthur in 1915, when he was 21 and she was 34. Louise Rieper had been born in India of English parentage and had been married previously. By the standards and conventions of the day, Louise Rieper sounds to have been an independent, unconventional woman and, perhaps, something of an adventurer.

The couple returned to New Zealand at the end of the War, settling in Napier on the Hawke's Bay, on the eastern shore of the North Island. The Riepers' first child, Kenneth Roy, was born in Napier in 1919 when Herbert was 25 and Louise was 37. They moved to Raetihi in 1922 and their second, Andre Louis, was born there in 1924, when Herbert was 29 and Louise was 43.

Herbert was working as a bookkeeper when he met Honorah Parker in Raetihi, around 1928. He was probably about 35 when he left his family and took up with Honorah. Louise was about 47 at the time and their children were about 10 and 6. Honorah was about 20. However, Herbert Rieper testified in the trial that these things happened two years later; Herbert probably calculated at some point before the trial that Honorah was under the age of majority (21) when they took up together, so came to claim they had been together for 23 years, not 25, as he had previously said in interviews. Note the symmetry in age differences; Louise was to Herbert as Herbert was to Honorah.

Herbert was working as a bookkeeper when he met Honorah Parker in Raetihi, around 1928. He was probably about 35 when he left his family and took up with Honorah. Louise was about 47 at the time and their children were about 10 and 6. Honorah was about 20. However, Herbert Rieper testified in the trial that these things happened two years later; Herbert probably calculated at some point before the trial that Honorah was under the age of majority (21) when they took up together, so came to claim they had been together for 23 years, not 25, as he had previously said in interviews. Note the symmetry in age differences; Louise was to Herbert as Herbert was to Honorah. Herbert and Louise Rieper were never divorced, which was the reason why he and Honorah Parker were never married. Herbert Rieper apparently paid some maintenance to his first family but had little contact with them.

Herbert and Louise Rieper were never divorced, which was the reason why he and Honorah Parker were never married. Herbert Rieper apparently paid some maintenance to his first family but had little contact with them. By 1936, Herbert Rieper and Honorah Parker had moved to Christchurch. They eventually had 4 children: Herbert, Wendy, Pauline and Rosemary. The fact that Herbert and Louise Rieper were never divorced is probably the reason why the house at 31 Gloucester St was put in Honorah Parker's name; this would ensure that Honorah and her children would retain the house if Herbert were to die.

By 1936, Herbert Rieper and Honorah Parker had moved to Christchurch. They eventually had 4 children: Herbert, Wendy, Pauline and Rosemary. The fact that Herbert and Louise Rieper were never divorced is probably the reason why the house at 31 Gloucester St was put in Honorah Parker's name; this would ensure that Honorah and her children would retain the house if Herbert were to die. Glamuzina and Laurie describe Herbert Rieper as a quiet, polite and dapper little man. In 1954, Herbert Rieper was the manager of Dennis Brothers' fish shop on Hereford St in Christchurch. He was 61 years old, so would have been close to retirement under better economic circumstances. Perhaps Herbert Rieper's impending retirement and the loss of income that would come with it was one of the financial pressures on the Rieper household which drove Honorah to take in boarders. Perhaps the family wanted to pay off the house before Herbert retired. Money worries were obviously an extremely important factor in the equation, contributing greatly to the atmosphere in the Rieper home. I tend to think that they were more prominent and important than has been emphasized in treatments to date.

Glamuzina and Laurie describe Herbert Rieper as a quiet, polite and dapper little man. In 1954, Herbert Rieper was the manager of Dennis Brothers' fish shop on Hereford St in Christchurch. He was 61 years old, so would have been close to retirement under better economic circumstances. Perhaps Herbert Rieper's impending retirement and the loss of income that would come with it was one of the financial pressures on the Rieper household which drove Honorah to take in boarders. Perhaps the family wanted to pay off the house before Herbert retired. Money worries were obviously an extremely important factor in the equation, contributing greatly to the atmosphere in the Rieper home. I tend to think that they were more prominent and important than has been emphasized in treatments to date.The public was, obviously and justifiably, extremely sympathetic to Herbert Rieper after the murder of his wife, and all people associated with the case appear to have been extremely reluctant to offer any criticism of him. This has continued in the discussion and analysis of the case since then, including, to a large degree, Glamuzina and Laurie's book. However, and no matter how much he may have loved them, it seems apparent to me from his statements and his testimony that Herbert Rieper probably had very little to do with the actual rearing of his children or with disciplining them. He may not have been an 'absent' parent, but he was probably very much of the 'hands-off' variety, preferring to leave such things to his wife. For example, Medlicott was obviously frustrated by the extremely vague and limited information about Pauline's medical history which he could glean from Herbert Rieper. His sketchy information to Medlicott about his daughter, conisting mostly of information about how she helped him with his hobbies and bare-bones facts about her illness, should be contrasted with Hilda Hulme's detailed information to Medlicott about her daughter.

Herbert Rieper testified in the Hearing and Inquest on July 16, 1954 that he himself played a critical role in the events from Easter, 1954, up to Honorah's murder but, by the time of the trial, his name was mostly absent and it was clear that Honorah Parker initiated and carried through with many of the actions and decisions concerning Pauline. Unfortunately, this 'hands off' approach of his made Herbert a very unreliable witness when it came to details of dates and even the sequence of key events. He said that Honorah finally approached Henry Hulme some time after Easter, 1954, determined to secure Henry's cooperation to break up the friendship of Pauline and Juliet. Around that time, the Riepers learned of Henry Hulme's plan to take Juliet to South Africa. It isn't clear what Herbert Rieper learned about the Hulmes' personal situation at that time. This is a crucial time period in the case, with few entries available from Pauline's diaries.

Herbert Rieper's experiences on the day of his wife's murder were truly heart-wrenching and tragic. He was out of the shop and missed the message that his wife had been "hurt," so didn't show up to Victoria Park until after work, two hours after his wife's death, driven by a colleague. He was the prime suspect, briefly, and was kept in the dark about what had happened to Honorah for several hours while being interrogated quite aggressively by police officers at the scene. Officers secured his permission to interrogate his daughter without legal counsel, and to search his house and her room under the same conditions, thereby having him sow the legal seeds of the extraordinary trial. He was obliged to divulge his marital status and that of Honorah Parker and the legal status of his children, all dutifully recorded and then reported worldwide the following day. And, the following day, Herbert Rieper was required to identify his wife's body--which must have been a particularly unpleasant and traumatic experience because of the nature of Honorah's injuries. He held the funeral for his wife the very next day, on thursday June 24, 1954.

Herbert Rieper's experiences on the day of his wife's murder were truly heart-wrenching and tragic. He was out of the shop and missed the message that his wife had been "hurt," so didn't show up to Victoria Park until after work, two hours after his wife's death, driven by a colleague. He was the prime suspect, briefly, and was kept in the dark about what had happened to Honorah for several hours while being interrogated quite aggressively by police officers at the scene. Officers secured his permission to interrogate his daughter without legal counsel, and to search his house and her room under the same conditions, thereby having him sow the legal seeds of the extraordinary trial. He was obliged to divulge his marital status and that of Honorah Parker and the legal status of his children, all dutifully recorded and then reported worldwide the following day. And, the following day, Herbert Rieper was required to identify his wife's body--which must have been a particularly unpleasant and traumatic experience because of the nature of Honorah's injuries. He held the funeral for his wife the very next day, on thursday June 24, 1954. In the week after the burial he placed a little add in 'the Press' on monday June 30, 1954, stating "Mr Rieper, Wendy, and Mrs Parker wish to Thank all their friends for their expressions of sympathy in their bereavement, and wish them to accept this as a personal acknowledgement."

In the week after the burial he placed a little add in 'the Press' on monday June 30, 1954, stating "Mr Rieper, Wendy, and Mrs Parker wish to Thank all their friends for their expressions of sympathy in their bereavement, and wish them to accept this as a personal acknowledgement." Herbert Rieper was apparently affected greatly by Honorah Parker's murder. He provided rather sketchy background information about Pauline to police and psychiatrists after his daughter's arrest. He testified at both the inquest and trial, but did not bother to attend the trial after his testimony was over. His testimony was not particularly informative and it is quite painful to read; it must have been unbearable to listen to him give it. Herbert Rieper refused to attend court on the day his daughter was convicted of murder, and stated from his home that he "had nothing to say" at the close of the trial. Reading between the lines, Herbert Rieper became terribly bitter and hostile toward the Hulmes and his daughter.

Herbert Rieper was apparently affected greatly by Honorah Parker's murder. He provided rather sketchy background information about Pauline to police and psychiatrists after his daughter's arrest. He testified at both the inquest and trial, but did not bother to attend the trial after his testimony was over. His testimony was not particularly informative and it is quite painful to read; it must have been unbearable to listen to him give it. Herbert Rieper refused to attend court on the day his daughter was convicted of murder, and stated from his home that he "had nothing to say" at the close of the trial. Reading between the lines, Herbert Rieper became terribly bitter and hostile toward the Hulmes and his daughter.The trial placed an extreme financial burden on Herbert Rieper. He was still paying legal fees many years later; these were reduced when the legal firm became aware of his hardship.

Herbert Rieper apparently had little to do with his daughter after the murder. He visited Pauline once in prison, but found the process "depressing". It is doubtful that father and daughter ever reconciled, and there is no record that they had any contact after Pauline's release on parole. When his daughter was released from prison in 1959, Herbert Rieper was quoted as saying about the sentence served by Pauline and Juliet: "It still doesn't make up for robbing a person of their life. It was evil between them that did it. Pure evil".

Herbert Rieper died in Christchurch in 1981, at the age of 92, after a long battle against pneumonia, a disease which figures prominently in this story.

Honorah Parker

Honorah Mary Parker was born in 1909 to Robert William Parker, a chartered accountant, and Amy Lilian Parker, in Birmingham, England. Birmingham is in the industrial Midlands of England, traditionally an economically depressed region of the country during this century, but Robert Parker's profession would have placed his family on the lower end of the working middle classes. In an interesting and, I think, very significant twist of fate, Honorah Parker and Henry Hulme were born less than a year apart, not all that far from each other in the geography of their birthplaces and quite close in terms of the social stations of their families. It would have been inconceivable for Honorah Parker not to be aware of these things even if she and Dr Hulme never broached the subjects and they may have been extremely important factors in determining Honorah Parker's attitudes toward the Hulmes. It is hard to believe that Honorah would not have dwelt upon the similarities in their beginnings in life and the huge disparities between her lot in life and Henry Hulme's. It is equally hard to believe, given her background, that Honorah would not have taken considerable satisfaction in Dr Hulme's fall from grace and from the revelation of his 'tainted' family situation.

Honorah Mary Parker was born in 1909 to Robert William Parker, a chartered accountant, and Amy Lilian Parker, in Birmingham, England. Birmingham is in the industrial Midlands of England, traditionally an economically depressed region of the country during this century, but Robert Parker's profession would have placed his family on the lower end of the working middle classes. In an interesting and, I think, very significant twist of fate, Honorah Parker and Henry Hulme were born less than a year apart, not all that far from each other in the geography of their birthplaces and quite close in terms of the social stations of their families. It would have been inconceivable for Honorah Parker not to be aware of these things even if she and Dr Hulme never broached the subjects and they may have been extremely important factors in determining Honorah Parker's attitudes toward the Hulmes. It is hard to believe that Honorah would not have dwelt upon the similarities in their beginnings in life and the huge disparities between her lot in life and Henry Hulme's. It is equally hard to believe, given her background, that Honorah would not have taken considerable satisfaction in Dr Hulme's fall from grace and from the revelation of his 'tainted' family situation.At the age of 18, in 1927, Honorah Parker emigrated to New Zealand with her mother, Amy. The fate or circumstances of Honorah's father aren't known. Honorah settled in Raetihi, NZ, where she eventually met Herbert Rieper, fifteen years her senior and an accountant in the firm where Honorah worked. This description of him makes Herbert Rieper sound like a reasonable approximation to Honorah's father, of course. Something to ponder.

According to trial testimony, some time between 1929, when Honorah was about 20 and under the age of majority, and 1931, Honorah Parker and Herbert Rieper began their relationship and began living together as husband and wife. They were never married, a fact eventually known only to themselves and adults in their immediate families. See the section on Herbert Rieper above for more on this part of their lives.

By 1936, Honorah Parker and Herbert Rieper had moved to Christchurch, NZ, living as husband and wife on Mathesons Road in the Phillipstown area of the city, described as "industrial" by Glamuzina and Laurie, but in many respects it seems to have become Honorah and Herbert's 'neighbourhood'. Mathesons Road lies outside the eastern border of the old town, a couple of blocks north of Lancaster Park and the railway tracks. Hereford St, where Herbert Rieper managed Dennis Brothers' Fish Supply, was two blocks to the north. There was a Methodist Church one block north, on Cashel St and Bromley Methodist Cemetery lay a short distance farther east, across Linwood Park and Linwood Ave.

Honorah's first child with Herbert was a boy, born a 'blue baby', in 1936, with cardio-pulmonary defects and he died almost immediately after birth. Their second child, Wendy Patricia Parker, was born in March 1937, when Honorah was 28 and Herbert 42. Pauline Yvonne Parker was Honorah's third child, born May 26, 1938, when Honorah was 29.

Honorah's first child with Herbert was a boy, born a 'blue baby', in 1936, with cardio-pulmonary defects and he died almost immediately after birth. Their second child, Wendy Patricia Parker, was born in March 1937, when Honorah was 28 and Herbert 42. Pauline Yvonne Parker was Honorah's third child, born May 26, 1938, when Honorah was 29.

During WW II, Pauline had severe health problems which would have placed serious financial strain on the family. In october 1942 Honorah Rieper passed in the examination on Elementary Home Nursing, perhaps in view of Pauline's illness.

During WW II, Pauline had severe health problems which would have placed serious financial strain on the family. In october 1942 Honorah Rieper passed in the examination on Elementary Home Nursing, perhaps in view of Pauline's illness.Nevertheless, in 1946, Honorah Parker and Herbert Rieper purchased a house on 31 Gloucester St, about 3 km west of Mathesons Road, near Hagley Park in the old town and sited between Canterbury College and CGHS.

The house was registered in Honorah Parker's name as "the wife of Herbert Rieper." There may have been compelling legal reasons not to register the house in Herbert's name. The Riepers apparently had a family lawyer, Dr A Haslam. He would eventually defend Pauline Parker for the murder of her mother.

The house was registered in Honorah Parker's name as "the wife of Herbert Rieper." There may have been compelling legal reasons not to register the house in Herbert's name. The Riepers apparently had a family lawyer, Dr A Haslam. He would eventually defend Pauline Parker for the murder of her mother.Honorah and Herbert had a fourth child, Rosemary Parker, in March 1949, when Honorah was 40 and Herbert was 54. Rosemary was born with Downs' Syndrome and her disability was severe enough for her to be institutionalized at the age of two or three by her parents. Rosemary was sent to Templeton Farm outside Christchurch, where she was visited regularly by her family and brought home for occasional visits, according to testimony.

Pauline Parker was said to have been very fond of Rosemary.

Pauline Parker was said to have been very fond of Rosemary.Honorah's mother, Amy, was a frequent guest at the Rieper house, though she apparently lived elsewhere in Christchurch. Herbert might have called her 'Mother Parker'. Pauline called her Nana Parker; 'Nan' or 'Nana' was and is a common term for grandmother in parts of England, especially among working- or lower-middle class people. The Hulmes probably would have used the term 'Gran' or 'Granny'.

Honorah took in boarders at 31 Gloucester St and ran the house as a boarding house. Unfortunately, it isn't clear when Honorah began taking in boarders, but it is actually possible that she began as late as January 1953, judging by some of Pauline Parker's diary entries. Pauline stated that her mother was going to take in 'Training School' boarders; these would have been Teachers' Training School pupils so Pauline may have had role models and an environment that was reasonably stimulating, intellectually, with these boarders. These are extremely important points, overlooked in all accounts I have seen. With their home so close to Canterbury College, it would also have been natural for the Riepers to take in College students, although College students did have the reputation of being rowdy.

Honora, Wendy and Herbert were contributing financially to the family during the time period seen in "Heavenly Creatures". Pauline was not, though there were apparently plans in the air for her to start pulling her weight in the family; Pauline was apparently due to start work the week of Juliet Hulme's planned departure.

Glamuzina and Laurie conclude, on the basis of diary entries largely referred to but not quoted, that there was considerable friction and conflict between Honorah and Pauline Parker and that it was quite longstanding. They conclude that Honorah may have slapped Pauline several times in one episode, but that Honorah apparently did not indulge in "excessive corporal punishment" when it came to disciplining her daughter. Glamuzina and Laurie conclude that the mother-daughter dynamics and relationships in both the Rieper and the Hulme households were the most important co-factors in the "Parker Hulme" murder, the ones responsible for defining who was murderer and who was victim. The primary aggravating factors, they claim, were the circumstances and stresses brought about by the disintegration of the Hulme household.

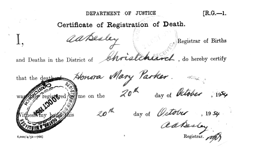

Glamuzina and Laurie conclude, on the basis of diary entries largely referred to but not quoted, that there was considerable friction and conflict between Honorah and Pauline Parker and that it was quite longstanding. They conclude that Honorah may have slapped Pauline several times in one episode, but that Honorah apparently did not indulge in "excessive corporal punishment" when it came to disciplining her daughter. Glamuzina and Laurie conclude that the mother-daughter dynamics and relationships in both the Rieper and the Hulme households were the most important co-factors in the "Parker Hulme" murder, the ones responsible for defining who was murderer and who was victim. The primary aggravating factors, they claim, were the circumstances and stresses brought about by the disintegration of the Hulme household.Honorah Mary Parker was 45 when she was murdered by her daughter, Pauline, and by her daughter's friend, Juliet Hulme, on Tuesday June 22, 1954. At the time of her murder, Honorah Parker was described as a quite ordinary, greying, middle-aged woman with dentures, much like anyone's mother. Really, though, very little is known of Honorah Parker; she died very much a plain, invisible woman who was transformed, almost immediately upon her tragic death, into things she probably had not been in life. These new and re-worked fragments of the real woman were trotted out and displayed and used by people with vested interests in the case, which makes re-constructing the real person difficult. On Thursday, June 24, 1954, Honorah Parker's body was cremated, after funeral services were held at Bromley Methodist Cemetery, back in the old neighbourhood.

Wendy Rieper

Wendy Patricia Parker was born in March 1937, she was aged 17 in 1954 during the trial of her younger sister Pauline. Dr. Medlicott described her as: "An attractive blonde of seventeen years of age. She is of average intelligence, likeable in manner, sociable and keen on sport, and has never given her family any cause for concern. Of different temperament than Pauline they have never had much in common". In 1957, three years after the trial, Wendy's engaged with Phillip William Norton. Apparently she's still using the 'Rieper' family name.

In 1957, three years after the trial, Wendy's engaged with Phillip William Norton. Apparently she's still using the 'Rieper' family name.In 1997, when Pauline is found living as Hilary Nathan in Kent, Wendy is interviewed. From two different sources:

* Wendy speaking from New Zealand, said, "She has led a good life and is very remorseful for what she's done. She committed the most terrible crime and has spent 40 years repaying it by keeping away from people and doing her own little thing." Wendy, a year older than Pauline, still finds it hard to explain why her sister and Juliet lured Mrs Honora Parker into a Christchurch park and took turns clubbing her to death.

"She has never spoken to me about the details of the way she took our mother's life. Well it was absolutely overboard, wasn't it? The story is: they met, they were ill-fated and they committed a dreadful crime".

* According to her sister Wendy, Parker is living the life she always dreamed of as a girl. Wendy said at her home in New Zealand: "In general she has led a law-abiding life, and now deeply regrets what happened all those years ago. The crime she committed was terrible, but she has been paying her debt to society for 40yrs by keeping away from other people and getting on with her own life".

Parker took five years to realise the enormity of her crime, said Wendy, but now is so repentant she spends most of her time praying.

From the Daily Mail in april 2023:

This week, a source in New Zealand said Pauline's sister Wendy — whose mother, after all, had been killed by her sister — forbade her children from having any direct contact with their aunt, even though she would send gifts to her nephews and nieces.

'There were no phone calls or visits because Wendy didn't want that to happen, although I know at least one of the children would have loved to have spoken to her,' they said.

Pauline's family in New Zealand, however, remain scarred by their past.' [Her nephew and niece] saw the terrible effect the murder and the story of it had on their mother, something she had had to put up with her whole life,' said a source.

'Every time it was brought up it would cut her in half.'

'It's been a burden the children themselves have borne their whole lives. They may have families and good careers, but are guarded, socially, because of the legacy the murder has.'

Sources:

- the Heavenly Creatures F.A.Q.

- Peter Graham, 'Anne Perry and the Murder of the Century' originally published as 'So Brilliantly Clever', 2011

- https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12026727/How-Anne-Perry-helped-best-friend-batter-mother-death.html