Hulme/Perry family

The Hulme family came to New Zealand in 1948. In the short period of only six years the family completely disintegrated. By 1954 Henry Hulme has lost his job and his marriage, he left the country with his ten year old son Jonathan, Hilda has changed her name to Perry and has left the country with Walter 'Bill' Perry, and Juliet is in jail, convicted of murder.

The Hulme family came to New Zealand in 1948. In the short period of only six years the family completely disintegrated. By 1954 Henry Hulme has lost his job and his marriage, he left the country with his ten year old son Jonathan, Hilda has changed her name to Perry and has left the country with Walter 'Bill' Perry, and Juliet is in jail, convicted of murder.

Henry Hulme

Henry Rainsford Hulme was born on August 9, 1908 in Southport, England to James Rainsford Hulme and Alice Jane Smith. These were modest beginnings, and Henry Hulme's family was not part of the social elite. His quite ordinary start in life may have left an indellible impression on Henry Hulme and may have driven him during much of his adult life.

Henry Rainsford Hulme was born on August 9, 1908 in Southport, England to James Rainsford Hulme and Alice Jane Smith. These were modest beginnings, and Henry Hulme's family was not part of the social elite. His quite ordinary start in life may have left an indellible impression on Henry Hulme and may have driven him during much of his adult life.Henry Hulme was admitted to Manchester Grammar School, a highly regarded 'magnet' Public School (private high school in the English system) for the best and brightest. He was sufficiently proud of his career at Manchester Grammar to list it in his official biography material, and being admitted to Manchester Grammar was probably Henry Hulme's first big career break, at the age of twelve. Reading between the lines of his Curriculum Vitae, Henry Hulme was a very determined and ambitious man, as well as being a very intelligent and able one, and he made several career moves during his life which appear to have been designed to effect quick advancement and generate recognition and respect.

Obviously in the top academic track, Henry Hulme went from Manchester Grammar on to Gonville and Caius College at Cambridge University, where he was to study at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. After being awarded his BA (Math Tripos) in 1929, at the age of 20, Henry Hulme went on to do graduate work in the early 30s, an exciting time for physics, and at Cambridge, an exciting place to be if you were a physicist. Lord Rutherford was an icon at Cambridge, then. Henry Hulme was Smith's Prizeman in 1931. After being awarded his doctorate in 1932, at 23, Dr Hulme spent time in Germany (possibly on a post-doctoral fellowship), studying at the University of Leipzig. Henry Hulme was in Germany at the same time as the prominent diarist Christopher Isherwood, whose "Berlin Stories" chronicled, through the eyes of an Englishman, the tremendous social unrest and upheaval that would come to sweep the Nazis to power. Dr Hulme returned to England and was a Lecturer in Mathematics at Liverpool University between 1936 and 1938.

Dr Hulme met Hilda Marion Reavley, possibly in Liverpool, and they married in June, 1937. He was almost 29 and she was 25, the daughter of a socially-prominent Anglican clergyman. In 1938, at age 30, Dr Hulme assumed the position of Chief Assistant at the Royal Observatory, and the Hulmes moved to Greenwich, a green and tranquil suburb of London, south and east of the central City, on the south bank of the Thames. The Royal Observatory is located in parkland, on a hill overlooking the Thames river valley. This is the location of the Greenwich Meridian, reference 'zero' for all lines of longitude, and time standards of the day. The Naval Academy is nearby, downhill, on the Thames. Dr Hulme's firstborn was a daughter, Juliet Marion, born in Greenwich October 28, 1938, as the stormclouds of war were gathering.

'On loan' to Whitehall and the Admiralty for the duration of World War II, and a rapidly-rising scientific advisor and administrator, Dr Hulme continued to live in Greenwich with his family, with serious consequences for the health and well-being of his wife and his daughter.

A son, Jonathan, was born on March 22, 1944. In August 1944, Dr Hulme travelled to America on war work. At the time, his wife was hospitalized with complications from the birth of their son, and his daughter was sent to the north of England to live. By the War's end, Dr Hulme was Director of Naval Operational Research.

A son, Jonathan, was born on March 22, 1944. In August 1944, Dr Hulme travelled to America on war work. At the time, his wife was hospitalized with complications from the birth of their son, and his daughter was sent to the north of England to live. By the War's end, Dr Hulme was Director of Naval Operational Research. After WW II, Dr Hulme became Scientific Advisor to the British Air Ministry from 1946 to 1948. On May 30, 1947, Lord Rutherford's alma mater, Canterbury University College, placed an advertisement for the newly-created position of full-time Rector, the top administrative position. Dr Hulme applied and, on November 18, the Universities Bureau of the British Empire forwarded their recommendation to the University of New Zealand for approval: Dr Henry Rainsford Hulme. A week later, around November 23, Dr Hulme was offered the position of Rector, Canterbury University College. He accepted and began to make plans for relocating himself, his wife and his son to New Zealand. His daughter was already out of the country, for the good of her health, and would be sent on ahead to New Zealand. In mid-1948, before taking up his new post as head of Canterbury College, Dr Hulme was honoured by his own alma mater, Cambridge University, with the award of the D.Sc. degree.

After WW II, Dr Hulme became Scientific Advisor to the British Air Ministry from 1946 to 1948. On May 30, 1947, Lord Rutherford's alma mater, Canterbury University College, placed an advertisement for the newly-created position of full-time Rector, the top administrative position. Dr Hulme applied and, on November 18, the Universities Bureau of the British Empire forwarded their recommendation to the University of New Zealand for approval: Dr Henry Rainsford Hulme. A week later, around November 23, Dr Hulme was offered the position of Rector, Canterbury University College. He accepted and began to make plans for relocating himself, his wife and his son to New Zealand. His daughter was already out of the country, for the good of her health, and would be sent on ahead to New Zealand. In mid-1948, before taking up his new post as head of Canterbury College, Dr Hulme was honoured by his own alma mater, Cambridge University, with the award of the D.Sc. degree.

Dr Hulme and his family arrived in Christchurch, NZ, on Saturday, October 16, 1948 and Dr Hulme became the first fulltime Rector of Canterbury University College. This was the position held by Dr Hulme during the period of time featured in "Heavenly Creatures". As Rector, which was the top administrative post at the College, Dr Hulme became a prominent member and a leader of Christchurch Society. The Hulmes moved into the Rector's official residence, Ilam, in early 1950. It was a spectacular colonial homestead and the site of many social functions attended by community leaders, such as the Anglican Bishop of Christchurch, politicians and even nationally- and internationally-prominent people, such as Lady Rutherford and the British actor Anthony Quayle.

Dr Hulme and his family arrived in Christchurch, NZ, on Saturday, October 16, 1948 and Dr Hulme became the first fulltime Rector of Canterbury University College. This was the position held by Dr Hulme during the period of time featured in "Heavenly Creatures". As Rector, which was the top administrative post at the College, Dr Hulme became a prominent member and a leader of Christchurch Society. The Hulmes moved into the Rector's official residence, Ilam, in early 1950. It was a spectacular colonial homestead and the site of many social functions attended by community leaders, such as the Anglican Bishop of Christchurch, politicians and even nationally- and internationally-prominent people, such as Lady Rutherford and the British actor Anthony Quayle. However, Dr Hulme's career as Rector did not begin well. Soon after his arrival, Dr Hulme alienated many of his colleagues on the faculty by voting against his own College Council "regarding the site of a proposed School of Forestry. ... His relationship with the College deteriorated steadily as other issues arose until finally, in mid March 1954, he was asked by his colleagues to resign" according to G&L, paraphrasing official University of Canterbury history. Actually, Dr Hulme submitted his resignation on March 4. There is a whole career's worth of events inbetween that beginning and that end, and a huge set of complicated forces and factors which defined the course of events. There may also have been other factors contributing to Dr Hulme's forced resignation.

However, Dr Hulme's career as Rector did not begin well. Soon after his arrival, Dr Hulme alienated many of his colleagues on the faculty by voting against his own College Council "regarding the site of a proposed School of Forestry. ... His relationship with the College deteriorated steadily as other issues arose until finally, in mid March 1954, he was asked by his colleagues to resign" according to G&L, paraphrasing official University of Canterbury history. Actually, Dr Hulme submitted his resignation on March 4. There is a whole career's worth of events inbetween that beginning and that end, and a huge set of complicated forces and factors which defined the course of events. There may also have been other factors contributing to Dr Hulme's forced resignation. Dr Hulme's family situation essentially self-destructed while he was Rector of Canterbury College. There have been published rumours that Dr Hulme may have had extra-marital dalliances during this time. Around the beginning of 1954, he eventually became party to an unusual living arrangement with Walter (Bill) Perry, his wife's lover, moving into Ilam. This was probably the final straw for his exasperated colleagues and a further incentive for them to demand Dr Hulme's resignation as Rector. It is clear that Dr Hulme also became preoccupied with his daughter's relationship with Pauline Parker in this same period, though just how 'serious' an issue it was to him isn't known.

Dr Hulme's family situation essentially self-destructed while he was Rector of Canterbury College. There have been published rumours that Dr Hulme may have had extra-marital dalliances during this time. Around the beginning of 1954, he eventually became party to an unusual living arrangement with Walter (Bill) Perry, his wife's lover, moving into Ilam. This was probably the final straw for his exasperated colleagues and a further incentive for them to demand Dr Hulme's resignation as Rector. It is clear that Dr Hulme also became preoccupied with his daughter's relationship with Pauline Parker in this same period, though just how 'serious' an issue it was to him isn't known. Dr Hulme's tremendous and very public fall from exalted grace, not to mention the extreme personal humiliation 'inflicted' upon him by people he trusted--his colleagues and his family--affected Dr Hulme greatly. It now seems clear that Dr Hulme eventually planned a bitter retreat from New Zealand with his children in tow, leaving his wife and her lover to their own devices. Apparently unwilling to parent his daughter and, it seems, loathe to leave her in his wife's custody, Dr Hulme planned to deposit Juliet in South Africa, on his way home to Britain with his son. In a critical and complex sequence of events. Dr Hulme tendered his resignation, discussed divorce with his wife, collected his essential possessions and made plans to steam home to England.

Then, just 12 days before the planned departure date, Dr Hulme's daughter, Juliet, helped her friend murder Honorah Parker.

Dr Hulme played an important role in the extraordinary events immediately after the murder, but it appears that he had reached the limit of what he would endure on behalf of his disintegrating family. The legal handling of Pauline and Juliet following the murder was very ill-conceived, bungled even, and it would seem that Dr Hulme adopted a completely 'hands off' attitude. Mere days after his daughter's arraignment, Dr Hulme said good-bye to his daughter, took his son, boarded the liner "Himalaya" bound for England and never looked back. He gave one press conference on board denouncing his daughter, the last public statement he was ever to make about the case. He did not provide significant evidence to the police, or testify at any legal proceeding or provide a deposition on behalf of either girl. He did not attend the hearing, the inquest or his daughter's trial for murder. In many ways, it is incredible that he was permitted to leave the country when he did. When Dr Hulme hit landfall in Marseilles, he disembarked and disappeared from public view, without comment.

Dr Hulme played an important role in the extraordinary events immediately after the murder, but it appears that he had reached the limit of what he would endure on behalf of his disintegrating family. The legal handling of Pauline and Juliet following the murder was very ill-conceived, bungled even, and it would seem that Dr Hulme adopted a completely 'hands off' attitude. Mere days after his daughter's arraignment, Dr Hulme said good-bye to his daughter, took his son, boarded the liner "Himalaya" bound for England and never looked back. He gave one press conference on board denouncing his daughter, the last public statement he was ever to make about the case. He did not provide significant evidence to the police, or testify at any legal proceeding or provide a deposition on behalf of either girl. He did not attend the hearing, the inquest or his daughter's trial for murder. In many ways, it is incredible that he was permitted to leave the country when he did. When Dr Hulme hit landfall in Marseilles, he disembarked and disappeared from public view, without comment. In 1955 Dr Henry Hulme made two brilliant career moves. First, he accepted a job at the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston in the United Kingdom, Britain's 'Los Alamos.' Second, he divorced his first wife and then married Margery Alice Ducker, daughter of Lady Cooper and her husband, a Peer of the Realm, Sir James A Cooper, KBE.

In 1955 Dr Henry Hulme made two brilliant career moves. First, he accepted a job at the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment at Aldermaston in the United Kingdom, Britain's 'Los Alamos.' Second, he divorced his first wife and then married Margery Alice Ducker, daughter of Lady Cooper and her husband, a Peer of the Realm, Sir James A Cooper, KBE.Dr Hulme devoted himself to physics once again and, three years later, in 1958, he became a proud father of Britain's thermonuclear Hydrogen Bomb, his third brilliant career move after leaving New Zealand. Dr Hulme made an extremely valuable contribution to Britain's becoming an independent nuclear power, restoring much of its faltering international prestige and clout. Remember, this was the height of the Cold War, the era of Sputnik and Soviet expansionism and the Suez Crisis. Britain had paid dearly for 'winning' the War with the Allies, by losing the last vestiges of the Empire, Palestine and much respect.

In 1959 Dr Hulme was appointed head of Nuclear Physics Research at Aldermaston and he remained in this important and politically-influential post through the 60s, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Test Ban Treaty (he was an important advisor on space-based detection schemes for verification), the Space Race, the global upheaval of 1968 and on into the era of Détente. He retired in 1973, at the age of 65. It is conceivable that Henry Hulme may have had the clout, in late 1959, to influence events in New Zealand, at least to the extent of having his daughter's case reviewed at her twenty-first birthday, but there is no evidence that he interfered in any way.

In 1959 Dr Hulme was appointed head of Nuclear Physics Research at Aldermaston and he remained in this important and politically-influential post through the 60s, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Test Ban Treaty (he was an important advisor on space-based detection schemes for verification), the Space Race, the global upheaval of 1968 and on into the era of Détente. He retired in 1973, at the age of 65. It is conceivable that Henry Hulme may have had the clout, in late 1959, to influence events in New Zealand, at least to the extent of having his daughter's case reviewed at her twenty-first birthday, but there is no evidence that he interfered in any way.In 1974 Henry Hulme was recognized by an invitation to join the socially elite ranks of the original "Who's Who." His biography is analyzed in section 7.10.1. The inescapable conclusion of that analysis is that Henry Hulme chose to completely obliterate all record of Hilda Marion Reavley from every official account of his life. In so doing, he also discarded his children and heirs from his biography. His second wife, Margery, died in 1990 and Dr Hulme himself died within the year, on January 8, 1991, at the age of 82.

There is evidence that Dr Hulme reconciled with his daughter in the years before his death. He did not change his official biography, however.

Hilda Marion Hulme

Hilda Marion Reavley was born in 1912 in England to a socially-prominent Anglican clergyman, the Rev J Reavley. She met and then married Henry Hulme in 1937, when she was 25, the year before Dr Hulme took up his post at Greenwich. Soon after moving to the green and pleasant London suburbs, Hilda bore Henry Hulme a daughter, Juliet, in late 1938. Hilda was 26. War broke out, and her husband was seconded by the Admiralty for war duty. Hilda and Juliet stayed with Dr Hulme, remaining an intact family, in London.

Hilda Marion Reavley was born in 1912 in England to a socially-prominent Anglican clergyman, the Rev J Reavley. She met and then married Henry Hulme in 1937, when she was 25, the year before Dr Hulme took up his post at Greenwich. Soon after moving to the green and pleasant London suburbs, Hilda bore Henry Hulme a daughter, Juliet, in late 1938. Hilda was 26. War broke out, and her husband was seconded by the Admiralty for war duty. Hilda and Juliet stayed with Dr Hulme, remaining an intact family, in London.Hilda Hulme testified in court that she was caught out in an air raid with Juliet when her daughter was two, and the harrowing experience had been extremely traumatic for Juliet, resulting in "bomb shock" and screaming nightmares which lasted many weeks.

Hilda Hulme bore her husband a son, Jonathan, on March 22, 1944, when Juliet was 5. Hilda Hulme testified that she had severe post-partum complications and had to be readmitted to hospital soon after returning home. The experience of waking to find her mother taken away in the night was said to have been very traumatic to Juliet, and was said to have coloured her attitude towards her brother and to have affected her later relationship with him. Hilda testified she was confined for some period in hospital, her illness too great to permit visitors, including her daughter. This would have been an unusual condition, though not if Hilda Hulme had also been suffering from severe post-partum depression, certainly common enough and even more understandable than under normal circumstances, given the uncertainty and violence of the war. In August, 1944, Dr Hulme had to go to America on war work and Hilda Hulme chose to send her daughter to the North of England, "because of her illness and the war conditions". War relocation of children and families from London to the countryside, or up north, was not uncommon, but it was always difficult.

Hilda Hulme chose to stay with her husband and young son when it became necessary to send her daughter away, alone, for the good of her health, first to the Bahamas and, later, to New Zealand. Almost a year after Dr Hulme was offered, and accepted, the post of Rector of Canterbury College, Hilda Hulme moved to New Zealand with Dr Hulme and Jonathan, arriving in Christchurch on October 16, 1948. She was reunited with her daughter around the time of Juliet's tenth birthday after a separation, this time, of about two years. In her trial testimony, Hilda Hulme said Juliet was demanding, very clinging and dependent and very difficult to discipline, at their reunion.

In Christchurch, Hilda Hulme became the pillar of the University community she was expected to be as the Rector's wife, and more. The couple became prominent in Christchurch Society, thanks to Henry's position but also thanks, in good measure, to Hilda Hulme's considerable work in the community. Hilda Hulme seems to have tackled her new duties body and soul.

In 1949, Hilda and Henry Hulme again sent Juliet Hulme away, for the good of her health, to a private boarding school in the North Island of New Zealand. Juliet would return within the year.

Also in 1949, Hilda Hulme joined the Christchurch Marriage Guidance Council, which had been formed the previous year, seen to be a "daring and progressive organization" [G&L] modelled after the British Marriage Guidance Council. The general principles of the Council stated [G&L] that the family unit was the basis of society, with permanent monogamous marriage the foundation of the family; everything possible should be done to prevent the tragedy of the broken home, and the train of evils which follow in its wake. Fertile unions should be promoted, and it was a firm belief that sexual intercourse should not take place outside of marriage. Hilda Hulme's work on the Marriage Guidance Council brought her into social contact with prominent members of Christchurch religious and professional establishment, with the Bishop of Christchurch, with psychiatrists and doctors (including Dr Bennett and Dr Bevan-Brown, who would later write on the case), Rex Abernethy (the magistrate who would preside over the arraignment of Pauline Parker) and even ST Barnett, who would become Minister of Justice and oversee the sentencing, incarceration, rehabilitation and eventual release of Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme.

Soon after Hilda Hulme joined the Christchurch Marriage Guidance Council, she organized a series of lectures giving advice to engaged couples. She was elected the Council's representative on the Canterbury Council of Social Services in 1950, the year the Hulme family relocated to Ilam. Hilda Hulme was also an active and popular marriage counsellor, highly regarded by her peers. She attended a training course for social workers in Wellington in 1952, the same year she was elected one of the Vice-Presidents of the Council. Hilda Hulme was re-elected a Guidance Council Vice-President in April 1953 and again in March 1954 and she remained a very active member until her resignation from the Council in May, 1954. The need for Hilda Hulme to resign from the Council was precipitated by her increasingly-public relationship with Walter Perry and the whole business stunned Council members. By then, Hilda Hulme had managed to break nearly every fundamental, founding principal of the Council, and add a few more serious conflicts of interest for good measure, over the space of six months.

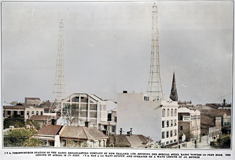

Soon after Hilda Hulme joined the Christchurch Marriage Guidance Council, she organized a series of lectures giving advice to engaged couples. She was elected the Council's representative on the Canterbury Council of Social Services in 1950, the year the Hulme family relocated to Ilam. Hilda Hulme was also an active and popular marriage counsellor, highly regarded by her peers. She attended a training course for social workers in Wellington in 1952, the same year she was elected one of the Vice-Presidents of the Council. Hilda Hulme was re-elected a Guidance Council Vice-President in April 1953 and again in March 1954 and she remained a very active member until her resignation from the Council in May, 1954. The need for Hilda Hulme to resign from the Council was precipitated by her increasingly-public relationship with Walter Perry and the whole business stunned Council members. By then, Hilda Hulme had managed to break nearly every fundamental, founding principal of the Council, and add a few more serious conflicts of interest for good measure, over the space of six months. In 1951 Hilda Hulme was a regular panel member of the Women's Session program on "3YA", one of the local radio stations. The panels discussed topics of the day, including religious instruction in schools, whether or not compulsory school uniforms were necessary, raising children etc and recordings of the discussions were exchanged with other stations.

In 1951 Hilda Hulme was a regular panel member of the Women's Session program on "3YA", one of the local radio stations. The panels discussed topics of the day, including religious instruction in schools, whether or not compulsory school uniforms were necessary, raising children etc and recordings of the discussions were exchanged with other stations. Hilda Hulme was also elected to the Board of Christchurch Girls' High School, which her daughter Juliet and Pauline Parker would attend--additional pressure on the girls to keep up appearances as model pupils, and additional pressure on the Hulme family when the girls blithely went their own way, according to G&L. Hilda Hulme tried to intervene, as a Board member, when Pauline Parker left school at her mother's insistence.

Hilda Hulme was also elected to the Board of Christchurch Girls' High School, which her daughter Juliet and Pauline Parker would attend--additional pressure on the girls to keep up appearances as model pupils, and additional pressure on the Hulme family when the girls blithely went their own way, according to G&L. Hilda Hulme tried to intervene, as a Board member, when Pauline Parker left school at her mother's insistence.According to Pauline Parker's diary entries, it appears as if Hilda Hulme grew quite fond of Pauline, but there may have been more to their relationship than the elements chronicled by Pauline on paper. For example, Hilda Hulme testified that she was led to believe that Pauline Parker was often subjected to severe corporal punishment at home, that Pauline was very unhappy at home and that her mother did not understand or love her. Indeed, Glamuzina and Laurie believe that the relationship between Hilda Hulme and Pauline Parker, and especially Hilda's actions and words to Pauline, are key to understanding the murder.

In mid 1953, Hilda Hulme traveled back to Britain with her husband while her daughter was confined with TB in Christchurch Sanatorium. Soon after the Hulmes' return to New Zealand in late August, 1953, Hilda Hulme met Walter Perry, through her work as a counsellor with the Marriage Guidance Council; Perry was a client who came for counselling. Within a very few months, around Christmas 1953, Walter Perry would move into Ilam to live "as a threesome" with Henry and Hilda Hulme.

Hilda Hulme's whirlwind relationship with Walter Perry apparently sealed the breakdown of her marriage and set into final motion a number of important events, including the generation of public pressure on both herself and Henry Hulme. Pauline Parker's diaries indicated that Pauline was initially shocked and distressed by this set of developments, but not hostile towards Hilda Hulme. Divorce was discussed and, after a complicated sequence of events, it appears as if Hilda Hulme was not going to get custody of either of the two children, despite the fact that Henry Hulme was obviously not prepared to be a parent to his daughter, Juliet. Henry and Hilda Hulme made plans to divorce and Hilda Hulme and Walter Perry made plans to start a new life together, alone.

Then, 12 days before the Hulme family was to be scattered to the winds, Hilda Hulme's daughter, Juliet, helped Pauline Parker murder Honora Parker, Pauline's mother.

Hilda Hulme appears to have been in reasonable control of the situation on the evening following the murder, but she appears to have gone into a kind of shock, for all intents and purposes, soon after that. With her husband apparently abrogating all parental and spousal responsibility, Hilda assumed the lion's share of responsibility for her daughter's legal defense and many mistakes were apparently made. Hilda Hulme stood by her daughter in the face of extraordinary legal proceedings and in the searing glare of a publicity that few people have ever experienced. Walter Perry was also always present, supporting Hilda all the way. Although Hilda's actions would seem to be to her considerable credit, the real situation may be more complex than it appears, with credit and blame being more difficult to define and assign. There was no lack of tragedy, though.

Hilda Hulme appears to have been in reasonable control of the situation on the evening following the murder, but she appears to have gone into a kind of shock, for all intents and purposes, soon after that. With her husband apparently abrogating all parental and spousal responsibility, Hilda assumed the lion's share of responsibility for her daughter's legal defense and many mistakes were apparently made. Hilda Hulme stood by her daughter in the face of extraordinary legal proceedings and in the searing glare of a publicity that few people have ever experienced. Walter Perry was also always present, supporting Hilda all the way. Although Hilda's actions would seem to be to her considerable credit, the real situation may be more complex than it appears, with credit and blame being more difficult to define and assign. There was no lack of tragedy, though. Hilda Hulme was evicted from Ilam when her husband departed New Zealand with her son, at the beginning of July. She auctioned their possessions in July 1954 to raise money for trial expenses and lived with Walter Perry in the Hulmes' Port Levy house throughout the trial and for a brief period following it.

Hilda Hulme was evicted from Ilam when her husband departed New Zealand with her son, at the beginning of July. She auctioned their possessions in July 1954 to raise money for trial expenses and lived with Walter Perry in the Hulmes' Port Levy house throughout the trial and for a brief period following it.Hilda Hulme testified at all stages of the legal proceedings on behalf of her daughter, though tabloid (and even broadsheet) news accounts from the time make it clear that she was very close to complete nervous collapse many times during the proceedings. Hilda Hulme testified under subpoena. She was obliged to inform the world of her most intimate personal affairs, as well as those of her daughter, in a largely-pointless trial whose outcome could have been predicted ahead of time. Glamuzina and Laurie contend that Hilda Hulme may not have remained in the country for the legal proceedings had she not been forced to remain and give testimony, by law.

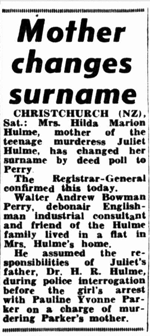

A few days after her daughter was convicted of murder and then sentenced to be detained During Her Majesty's Pleasure, Hilda Marion Hulme changed her name, legally, by deed poll in Christchurch, to H Marion Perry. She would be referred to as Mrs H Marion Perry from that point on.

A few days after her daughter was convicted of murder and then sentenced to be detained During Her Majesty's Pleasure, Hilda Marion Hulme changed her name, legally, by deed poll in Christchurch, to H Marion Perry. She would be referred to as Mrs H Marion Perry from that point on.

Less than a week later, she left New Zealand with Walter Perry, by steamer, never to return. As there had been with Henry Hulme, there was also a final press conference shipboard for Walter and H Marion Perry, denouncing Juliet. It was reported that H Marion Perry refused to discuss any aspect of the whole affair for many years. She never made another public statement about the case.

Less than a week later, she left New Zealand with Walter Perry, by steamer, never to return. As there had been with Henry Hulme, there was also a final press conference shipboard for Walter and H Marion Perry, denouncing Juliet. It was reported that H Marion Perry refused to discuss any aspect of the whole affair for many years. She never made another public statement about the case.Hilda Perry and Henry Hulme were divorced in 1955 and Hilda and Walter Perry were married, taking up residence in England but settling far from Henry Hulme. The couple remained together, taking in Juliet upon her release from prison. After Bill Perry died in 1986, Hilda—living in the Midlands and long since known as Marion Perry—took a job as a voluntary tutor at a college of further education, helping teach English as a second language, and remedial English to slow learners and stroke victims. She did not retire from this fulfilling work until she was eighty, when she moved to Portmahomack to be near her daughter. She bought a fisherman’s cottage with glorious views over Dornoch Firth to the mountains of Sutherland and came to love the wild beauty of the place.

By then she was suffering from arthritis and her eyesight was failing, but she still walked two or three miles a day and enjoyed pottering in her garden, feeding the seagulls that nested in her shed, and making new friends among the villagers. A visitor from New Zealand described her as “still charming and lively”. She missed her son Jonathan, who lived in Zimbabwe where he practised as a doctor, but he visited regularly and wrote to her often. It was a shock to her when he married a Chinese woman, but their two beautiful grandchildren became a great joy. She died in 2004 at the age of ninety-one.

Jonathan Hulme

Jonathan Hulme was born on March 22, 1944 in Greenwich. He was around the age of 10 when the murder happened. Directly after Dr Hulme sailed for England via Capetown and Marseilles with Jonathon on the vessel "Himalaya". They eventually ended up ik the UK again, where Jonathan had a relatively normal childhood. He later became a docter.

Jonathan Hulme was born on March 22, 1944 in Greenwich. He was around the age of 10 when the murder happened. Directly after Dr Hulme sailed for England via Capetown and Marseilles with Jonathon on the vessel "Himalaya". They eventually ended up ik the UK again, where Jonathan had a relatively normal childhood. He later became a docter.In march 2024 Jonathan gave a lenghty interview with a New Zealand reporter in which he stated that Juliet had 'No remorse, no understanding and a fragile hold on reality'. He remembers the day Honorah Parker died. His “bossy” older sister with the “wonderful imagination” had gone out for the day with her best - and by then only - friend. “Quite often when I saw her, there was Pauline hanging around,” he said. She was “a bit of a dark, unresponsive character”. “I never related much to her. I don’t remember much of Pauline, she tended to be in the background and didn’t communicate much to me. That’s the way she was.” He was in his bedroom listening to the radio - 3ZB, a weekly programme featuring Robert Fabian, a famous Scotland Yard detective. “My dad came in and he said ‘I have some important news I better tell you - there’s been a terrible accident. I’m afraid while Juliet and Pauline were out with Pauline’s mother, there was a terrible accident and Pauline’s mother has been killed,” Jonathan said. “My dad came back a few days later and told me that in fact, it wasn’t an accident that she’d been killed - and my sister and Pauline were responsible for killing her. “It took me a while to sort of figure out what that meant - but I could put that together.” By the time the trial started, Jonathan and his father had left New Zealand and he would not see his sister again for almost six years. “My dad kept me informed all the time about what was happening ... what happened to her was pretty darn brutal. For a 15-year-old girl to go to the toughest prison in the Southern Hemisphere - it is to her credit that she survived that. “She went through some pretty tough times. Lesser people would have pulled the plug on themselves, or given up. She didn’t.”

Jonathan Hulme said his sister’s return after prison was awkward. He had not heard directly from her since her arrest and was at college when she appeared back in his life. “Obviously, she was somebody who was now in a completely different environment and trying to find a beat. So everyone was a little bit cautious, a little bit wary,” he said. “But she was my sister, and we had a natural bond. “It took a bit of time for her to develop ... And then it was a question of just getting to know her. We didn’t talk about the past, then. I think we [were] too busy trying to establish the present and look to a future.”

Jonathan said his sister’s crime had a deep impact on his family and he experienced “moments of unhappiness and anger” over the years. “I think I was at times ... I was angry. I was unhappy for my parents’ sake. This was the biggest nightmare that you could possibly have as a parent,” he said. “They knew there was something wrong with the relationship with Pauline and that it was getting toxic but never in a month of Sundays would they have believed it would end in murder. It was horrendous.” Jonathan went on to study medicine while Juliet worked “odd jobs”. “We got on well ... we did become closer. But she did her thing and I had my life to lead,” he said. “It took her a while to establish herself and get her self-confidence back. “She went over to America, to LA. It was her lifelong dream that they [Juliet and Pauline] were going to go to Hollywood and be accepted and famous. It was an absolute fantasy, but my sister tried to make it real by going to Los Angeles. “Nothing ever really happened. She came back to England ... and she carried on writing ... that’s all she ever really wanted to do, and everything else was sort of marking time until she got accepted. “It was Bill Perry that suggested she write a novel that was in the time of Jack the Ripper - so she did that. And this was the first book that actually got anywhere.

“They eventually got round to make a television version of it. We got some decent actors and everything, and she actually got a walk-on part in it. She was quite chuffed with that. It did quite well, but it never really took off. “Ever since then, Juliet was hoping, hoping, hoping that there would be a silver screen version of the books that she had written. That never happened.”

Jonathan said over the years his sister had boyfriends and several marriage proposals but she could never settle down with anyone while she had such a deep secret. Once she was outed, Juliet carried on with her writing, her career as an author unimpacted by the revelation. While sometimes she would give a brief insight into her prison stint, she generally avoided speaking about the murder and trial.

Jonathan took a job with his sister when he moved his family back to the UK in the mid-2000s. Both of his children were nearing university age and he wanted to work again as a doctor. But his sister needed a personal assistant and he accepted the role, staying on for more than two decades. “It was a good job ... I’d come up there in the morning, get the emails off, print them off, take them to her. We would write the comments, discuss it, then I’d reply. And there’ll be various research things for me to do,” he said.

Jonathan took a job with his sister when he moved his family back to the UK in the mid-2000s. Both of his children were nearing university age and he wanted to work again as a doctor. But his sister needed a personal assistant and he accepted the role, staying on for more than two decades. “It was a good job ... I’d come up there in the morning, get the emails off, print them off, take them to her. We would write the comments, discuss it, then I’d reply. And there’ll be various research things for me to do,” he said. “We’d have lunch together at one o’clock and work through the afternoon. She would be back up in her office writing away. And I’d be on the computer or reading books … I had plenty to do.”

Jonathan avoided the media until his appearance in the documentary Anne Perry, Interiors - promoted as an inside look at the famed writer’s life. But he was not able to be authentic, he felt. It was yet another occasion where everyone involved had to stick to his sister’s script, her rules of engagement. Again, Jonathan watched as she “trotted out” her narrative that minimised her involvement, how she was “frightened” of Pauline and “absolutely trapped” into killing Honorah.

Jonathan never saw real remorse from his sister and any regret was not around the murder, but the consequences. “She admitted that what she had done was wrong. And she admitted that it was right that she was sent to prison. I do not remember her, at any time, expressing much remorse,” he said. “I think she was just captured by the moment - it was all rather jolly, I don’t think she really understood the seriousness of what she was doing. “When it came to the trial, the giggling and whispering and flirting and nodding to each other in court ... That showed that the seriousness of what had happened and the seriousness of where they were at escaped them.” Jonathan is in no doubt his sister should have been found not guilty by reason of insanity, adamant she was severely unstable at the time of the murder and remained unstable for the rest of her life. “It was a classic psychosis ... My sister’s fragile hold on reality remained … at times, she was a bit naive, gullible, gauche, a bit over the top ... narcissistic,” he said. “My sister had a gifted imagination, she ran on high-octane emotions and she loved to invent and create. In the right environment. That is good … in writing, that is what made her successful."

Jonathan never saw real remorse from his sister and any regret was not around the murder, but the consequences. “She admitted that what she had done was wrong. And she admitted that it was right that she was sent to prison. I do not remember her, at any time, expressing much remorse,” he said. “I think she was just captured by the moment - it was all rather jolly, I don’t think she really understood the seriousness of what she was doing. “When it came to the trial, the giggling and whispering and flirting and nodding to each other in court ... That showed that the seriousness of what had happened and the seriousness of where they were at escaped them.” Jonathan is in no doubt his sister should have been found not guilty by reason of insanity, adamant she was severely unstable at the time of the murder and remained unstable for the rest of her life. “It was a classic psychosis ... My sister’s fragile hold on reality remained … at times, she was a bit naive, gullible, gauche, a bit over the top ... narcissistic,” he said. “My sister had a gifted imagination, she ran on high-octane emotions and she loved to invent and create. In the right environment. That is good … in writing, that is what made her successful."“And in the the wrong environment, with a toxic influence, she was running insane … The end result is there were two people who found each other and it spiralled off into a psychotic, murderous climax. “She had a fragile hold on reality - and most people respected that. But when it becomes malignant as it did in relationship with Pauline, you end up with a murderer.” Jonathan firmly believed Juliet and Pauline were the victims of a miscarriage of justice - mainly due to the judge’s summing up and the pressurised verdict. “He pushed for a verdict of guilty. He was not prepared to accept insanity .... managed to dismiss the florid, flagrant, psychotic behaviour of these two young people,” he said. “To him, they were evil but they were not mad. They were evil, and always would be.”

Hear Jonathan speak for yourself:

Walter Perry

Walter Andrew Bowman Perry a.k.a. Bill Perry was born in Winnipeg, Canada. He was an engineer by training and profession.

Walter Andrew Bowman Perry a.k.a. Bill Perry was born in Winnipeg, Canada. He was an engineer by training and profession.Walter Perry moved to New Zealand in July 1953, while the Hulmes were abroad in England, at the direction of Associated Industrial Consultants, a British Company based in London. When Walter Perry's marriage broke up, he became a client of the Christchurch Marriage Guidance Coucil, where he met Hilda Hulme, some time after her return to Christchurch at the end of August, 1953. The two fell in love, in what must have been something of a whirlwind romance. Even disregarding Hilda Hulme's defiance of her 'scandalous' professional conflict of interest, the social disparity between Walter Perry and Hilda Hulme, and the time line surrounding their relationship are very important points to consider.

Hilda Hulme had an enormous amount of social standing to lose by undertaking a relationship with Walter Perry. Throwing away a lifetime's worth of respect and social standing is not something undertaken lightly or on the spur of the moment and the velocity of Walter and Hilda's relationship is highly suggestive of serious and longstanding domestic problems between Henry and Hilda Hulme. In effect, Walter Perry was probably more a catalyst of the upheaval to come than its cause, more a trigger than the reason. As things would turn out, this was not to be a casual and temporary fling for either Walter Perry or Hilda Hulme. In fact, their relationship would be tested to limits experienced by few people, and it would survive. To me, this indicates a genuine and rather deep emotional need in Hilda Hulme part which Walter Perry was apparently able to fulfill.

Around Christmas, 1953, Walter Perry moved into a semi-private flat at Ilam to live with the Hulmes. He had a private housekeeper, but she would be dismissed before Easter, 1954. Walter Perry's relationship with Hilda Hulme was apparently known to Henry Hulme and even accepted by Dr Hulme, according to testimony. The unusual living arrangement at Ilam generated significant gossip and social pressure, however, and it would precipitate the final breakup of Hilda and Henry Hulme's marriage. It also probably contributed to the forced resignation of Henry Hulme from his post as Rector of Canterbury College.

While at Ilam, Walter Perry was discovered in flagrante delicto with Hilda Hulme by Juliet Hulme around Easter, 1954. This event crystallized a family crisis with very wide-reaching repercussions because it occurred at a critical moment amidst several other key events:

* it was a few weeks after Dr Hulme received the letter asking for his resignation, so the three adults had already planned the breakup of the family,

* it was less than two weeks after Pauline's removal from school by her mother, and Pauline had been frustrated by her inability to get a job,

* it was just one day after Pauline's first day at Digby's Commercial College,

* it was just three days before Dr Hulme informed the girls of the plans for divorce but not the specific plans to remove Juliet from New Zealand.

The Easter event and ensuing crisis were well-documented by Pauline Parker and were entered into testimony during the trial, though Pauline's account was disputed by both Walter Perry and Hilda Hulme. There is no doubt that Walter Perry had become a significant presence and influence at Ilam by this time.

Significantly, Walter Perry was also very well-informed about the girls' activities and writings. Ilam was apparently a house with enormous numbers of poorly-guarded secrets. At the trial, he claimed that Juliet had shown and discussed with him some of her work; if true, it would indicate a more intimate relationship between the two than has generally been painted. Although it was claimed in the trial that he had been blackmailed by the girls, it seems pretty clear that there were no secrets between the three adults by this stage, so his giving money to Juliet was probably just an attempt to win her affection, the step-parent trap or, perhaps, it was a genuine attempt to soothe an obviously-troubled girl.

Within a month, Hilda Hulme was forced to resign her positions because of Walter Perry and Pauline Parker mentioned despair and suicide and the word murder for the first time. One diary entry after Easter quoted in the open press mentions Walter Perry, and it is an important one.

Walter Perry was still living at Ilam when Pauline and Juliet murdered Honora Parker on June 22, 1954.

On the evening following Honora's murder, Walter Perry was involved in several absolutely key events. First, at Hilda Hulme's request, Walter Perry took the girls' bloody clothing to a commercial dry cleaners before the arrival of the police. There have also been persistent rumours that Walter Perry was also involved in the destruction of other damning evidence that night, including Juliet Hulme's diaries and writings. Walter Perry also sedated both girls the evening of the murder, before they were interrogated by police. He was present at all but one critical interrogation session.

In addition, Walter Perry apparently advised both Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme to simply "tell the truth," without benefit of counsel, apparently with the blessing of Henry and Hilda Hulme. In a very real sense, then, it was Walter Perry who defined the defense strategy, because it was the girls' damning confessions which left the defense with few options.

When Henry Hulme left New Zealand a couple of weeks later, Hilda Hulme and Walter Perry were evicted from Ilam. They auctioned the Hulmes' private possessions to raise money for the defense and their expenses and they took up residence at the Hulmes' holiday home at Port Levy.

When Henry Hulme left New Zealand a couple of weeks later, Hilda Hulme and Walter Perry were evicted from Ilam. They auctioned the Hulmes' private possessions to raise money for the defense and their expenses and they took up residence at the Hulmes' holiday home at Port Levy.Walter Perry testified on behalf of Juliet Hulme at both the inquest and the trial, though his testimony was not much assistance to the defense. To his considerable credit, Walter Perry stood by Hilda Hulme emotionally and even physically throughout this period, apparently unconcerned about being photographed with Hilda Hulme after their relationship had been made public through testimony.

After the trial, Walter Perry left New Zealand for the UK with H Marion Perry. He made a statement to the press during the sea voyage which was disparaging to Juliet Hulme but which also expressed his concern for Hilda Hulme. That was his last public statement about the case. Walter Perry married H Marion Perry after her divorce from Henry Hulme. The couple settled in the UK.

After the trial, Walter Perry left New Zealand for the UK with H Marion Perry. He made a statement to the press during the sea voyage which was disparaging to Juliet Hulme but which also expressed his concern for Hilda Hulme. That was his last public statement about the case. Walter Perry married H Marion Perry after her divorce from Henry Hulme. The couple settled in the UK.

After Juliet Hulme was released from prison, she moved back to the UK and lived with Walter and H Marion Perry for a time. Juliet Hulme adopted the surname Perry (revealed in 1994) and, as Anne Perry, she listed Walter Perry as her father in her official biographies written before 1994. She now refers to "Bill" Perry, in public, as her stepfather.

After Juliet Hulme was released from prison, she moved back to the UK and lived with Walter and H Marion Perry for a time. Juliet Hulme adopted the surname Perry (revealed in 1994) and, as Anne Perry, she listed Walter Perry as her father in her official biographies written before 1994. She now refers to "Bill" Perry, in public, as her stepfather. Walter Perry died in 1986.

Sources:

- the Heavenly Creatures F.A.Q.

- Peter Graham, 'Anne Perry and the Murder of the Century' originally published as 'So Brilliantly Clever', 2011